By:

Melinda Underwood

|

Scotch and Toilet Water?

Of course, if Leo Cullum weren’t such a talented and insightful cartoonist, we wouldn’t have the new collection of dog cartoons Scotch and Toilet Water?. But it’s really New Yorker cartoon editor Bob Mankoff that we have to thank for so wisely advising Cullum to go to the dogs. The collection was published this year by Harry N. Abrams, Inc. and features 125 wry takes on contemporary life through a dog’s eye.

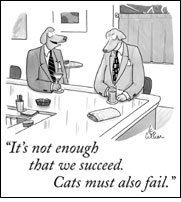

New Yorker aficionados will immediately recognize the dogs in suits, hanging out in bars advising each other (“First of all, forget everything you learned in obedience school.”), testifying in court (“How do you plead?” “Bad dog.”), and spreading canine mythology in the neighborhood (“It’s absolutely true. One FedEx driver is equal to three mailmen.”).

Most of all, Cullum’s dogs put us in our place, eviscerating our assumptions about dogs and lacerating our self-importance. One cartoon that has likely landed on many a refrigerator shows a startled middle-aged man just about to throw a stick when his dog says matter-of-factly, “O.K., just one more and then I’ve got to get on with my life.”

Before we get on with our lives, we have an opportunity to spend some time with Leo Cullum, to try to figure out the genius behind the dogs on the page.

U.D. Can you tell us a little about your history? How did you get your start?

L.C. I grew up in New Jersey but graduated from Holy Cross College in Worcester, MA in 1963. I went directly into the Marine Corps and wound up flying the F-4B fighter in Vietnam in 1966-67. Leaving the Marine Corps in 1968, I joined TWA and was based in New York.

The nature of flying for the airlines is that you have reasonably large blocks of time off and there was always a part of me that wanted to paint, draw or express myself in the arts somehow. I did some painting but was always a fan of magazine cartoons and it struck me that this was something I could do.

U.D. So one day you just decided to create cartoons?

L.C. Naturally, things look easy because experts make them look that way. I got all the books I could find on the subject and just started writing and drawing. The books told how and where to submit work and what the rates were.

It immediately became apparent to me that I had no style…. Just as your handwriting is recognizable as your own so should your drawings be – but if you haven’t been drawing a long time, your style tends to be all over the map.

U.D. So it was a bit of a rough start?

L.C. The good side was that I enjoyed the whole process – the writing (which seemed more like daydreaming than anything else), the drawing and the sending away (which would have appealed to anyone who grew up sending off box tops for prizes).

I don’t think my parents ever really “got” what I was doing. They knew me as a pilot (I was about 28 when I began drawing) who was doing some sort of drawings.

U.D. Did you quit your day job?

L.C. It wasn’t planned, but cartooning dovetailed beautifully with flying – both from the aspect that it travels light (papers, pencils, pens) and there are long layover times to fill in not always the most charming cities.

U.D. When did you get your first break?

L.C. The first drawing I sold was to the airline pilot’s magazine —drawing of a captain, first officer, and flight engineer. The flight engineer has a tiny head and huge flight manual bag. The first officer has an average head and bag. And the captain a huge head and tiny bag. This drawing must have struck a chord with crews because I heard comments about it for years.

U.D. Who were your primary influences?

L.C. Some early influences on my style were Charles Rodriguez, who had a very gritty realist look, and Charles Addams from the New Yorker. Other influences were Jack Ziegler, whom I met while making the rounds in New York to editor’s offices. Jack was just beginning also and was always good company. Sam Gross was also helpful – his work was everywhere and it seemed like a big deal to meet him.

U.D. Many people know you and your work through the New Yorker. It’s a notoriously competitive venue. How did you get entrée?

L.C. I started submitting to the New Yorker in the early 70s. This was a time when many of the older cartoonists would supplement their own ideas with ideas bought for them by the New Yorker. The so-called “gag writer” has now largely gone the way of the Dodo. At any rate, some of my ideas started to be purchased for re-draw, primarily by Charles Addams – major progress and a big thrill!

U.D. When did you get a room of your own, so to speak?

L.C. I was selling various other magazines drawings at this time but it wasn’t until 1977 that the New Yorker published one of my own drawings – bringing my gag writing status to a close. Before too long, I was under contract to the New Yorker and attending functions with those legendary old guys. I felt like the new second-string right fielder on the Yankees.

U.D. When did dogs first enter the picture?

L.C. The dog drawings must have started somewhere along the way – I don’t remember making any conscious decision to do a lot of dog drawings. But they have been responded to favorably.

I wanted to publish a general collection of my New Yorker work but Bob Mankoff suggested that a book of dog drawings might sell better. Part of the appeal of these cartoons is that so many people “speak dog,” in that they are familiar with the innumerable things dogs do and are: sit, speak, stay, roll over, fetch, bark, chase balls, sticks, postmen, cars, hunt, sleep, lay about, eat, make messes, keep us company, and on and on. Add these to human foibles and there is a lot of common ground.

U.D. How do your ideas come upon you? Any tricks for unlocking the muse?

L.C. I’m not really looking for dog ideas when I’m writing. They just show up. If anyone knew specifically and scientifically how to get ideas they would get thousands of them a week. It’s a little like looking for gold: turning over lots of rocks, sifting through lots of gravel, but there is a definite sense that you’re in the right area. It helps to feel funny – and one good idea begets another.

Most of my ideas originate with a phrase, perhaps some way people are now referring to something or some phrase the media has recently popularized: “gravitas,” “regime change,” “quality time,” etc. It’s very unscientific and when I’m at a dead end I start examining why I don’t feel funny, what is it that’s bothering me? Maybe there’s a cartoon idea in that somewhere.

I love seeing someone’s great idea in print but a close second to the joy of seeing it is the feeling “Why didn’t I think of that? It was there all the time just ripe for the picking!” Of course, some wonderful cartoonists have created such a personal world that you never get this feeling – because you couldn’t possible have come up with those ideas which are so interconnected with their fantasy world.

U.D. You’ve been published thousands of times. Do you still get a thrill when you see your work in print?

L.C. I do like to come across my work unexpectedly. My first thought is “Oh, good!”. My second thought is: “Was I paid for this?”. My third is “Does John Malkovich think this is funny?”

U.D. Can you tell us a little bit about the process of creating one of your cartoons?

L.C. It usually takes two or three drafts to get the drawing in decent shape. I send the New Yorker ten drawings by FedEx every Monday. They’re gone through on Tuesday. A few go into the art meeting on Wednesday and I’m told Thursday if I have any sales. By which time I’m into the next week’s work. If I’ve sold something, I do a “finish finish” on Bristol board and send it back with my new submissions and on and on. The unbought drawings are mine to sell elsewhere.

U.D. That sounds like a strenuous schedule – I don’t think a lot of people realize how much work it is to be funny! And that’s not all you do. You’re in advertising too, aren’t you?

L.C. I really consider advertising work to be secondary. It can be lucrative and interesting, but it can’t be depended upon. Sometimes there are several jobs going, but frequently none.

U.D. You often poke fun at lawyers and businessmen. I can’t imagine this, but do you ever take any hits for these portrayals?

L.C. I think attorneys actually do appreciate my jibes, or at least take it good-naturedly. I’m published regularly in the national law journal and haven’t received any death threats. (They know I’d sue their pants off!)

U.D. It seems like the cartoons in the books Scotch and Toilet Water? are, for the most part, timeless. I can imagine picking the book up in 20 years (which I will) and laughing all over again. Does most of your work have this quality?

L.C. I do a lot of very general (or “evergreen”) cartoons so they have a fairly long shelf life. I love selling a drawing I did 15 years ago.

I’ve drawn over 10,000 cartoons in my life and have no plans to slow down, but I still want to start painting! Right now I’m reading Composition of Outdoor Painting by Edgar Payne, a fabulous California plein aire painter who died around 1947.

U.D. Do dogs have a sense of humor?

L.C. I think dogs are very good-natured. I’m not sure they have a sense of humor, but I could be wrong. They say tragedy plus time equals comedy. Dogs just see old tragedy. I expect good behavior from my dogs, not laughs – though that wouldn’t hurt.

U.D. What role has humor played in your life?

L.C. As I said, I grew up in Jersey – North Bergen to be exact. We were street kids in that we only came home to eat and sleep. If you’re small, and not particularly athletic, it’s a huge help to be funny. It’s a survival technique.

I now live in Malibu, CA, about a mile up from the beach. It’s pretty and quiet and we have good restaurants. I have a wife, Kathy, and two daughters, Kimberly, 21, at UCLA, and Kaitlin, 16, at Malibu High School. I retired from flying in January 2002 after 34 years and yet I don’t seem to have any more free time!

For more information about Leo Cullum and his dog friends, be sure to check out the delightful introduction to Scotch and Toilet Water?.

|

|

|

|